Try Amazon Fresh

Barlaam and Ioasaph

The Holy Monastery of Iveron, Mount Athos, Greece, Codex. 463

Folio 3r

pp.242-243 The Glory of Byzantium : art and culture of the Middle Byzantine era, A.D. 843-1261, edited by Helen C. Evans and William D. Wixom. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

164. Barlaam and Ioasaph

Byzantine (Constantinople), ca. 1075-1125

Tempera and gold on vellum; 135 fols.

17 x 23 cm (9 x 6¾ in.)

CONDITION: The manuscript is defective at the end; scattered leaves are missing throughout; a later hand has obliterated evil figures.

The Holy Monastery of Iveron, Mount Athos, Greece (Cod. 463)

Barlaam and Ioasaph tells a fascinating story set in an exotic land. At some time during the early centuries of the Christian Church the pagan king of India, Abenner, undertakes to rid his kingdom of Christians. He isolates his only child, Ioasaph, to shield the boy from Christianity and from all earthly concerns. Eventually Ioasaph is released, but he is confronted by sickness and poverty. Responding to divine inspiration, Barlaam, a seventy-year-old monk, travels from his native Egypt and, disguised in secular clothing, gains entrance to the palace and to the prince, converting and baptizing him after a series of conversations. Finally reconciled to his son's faith, Abenner divides his kingdom into two parts; that which he has allocated to his son flourishes while his own falls into decline. Grasping the significance of the disparity, the king is converted to Christianity, then dies. Ioasaph renounces the throne to join Barlaam in the wilderness.

We do not know who wrote Barlaam and Ioasaph. It was not John of Damascus, with whom it has often been associated since the Middle Ages. Evidence points to the text's creation in the early ninth century in Palestine, probably in the milieu of the Great Lavra of Saint Sabas.1 For Christian monks living in Muslim Palestine the story would have given shape to their hopes for the conversion of the caliph following, as it does, a pattern known from medieval chronicles in which a non-Christian ruler converts and leads in the baptism of his people. The story of Barlaam and Ioasaph, in which elements of the life of the Buddha have been recognized, was immensely popular throughout the Middle Ages. At least 140 copies of the text in Greek are known, and of them 6 are extensively illustrated.

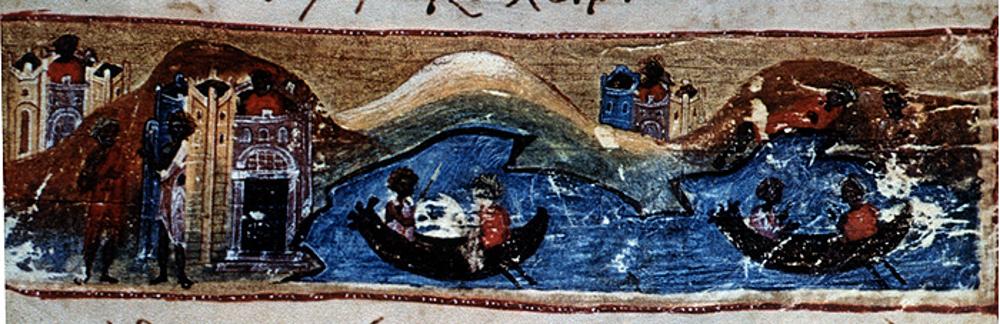

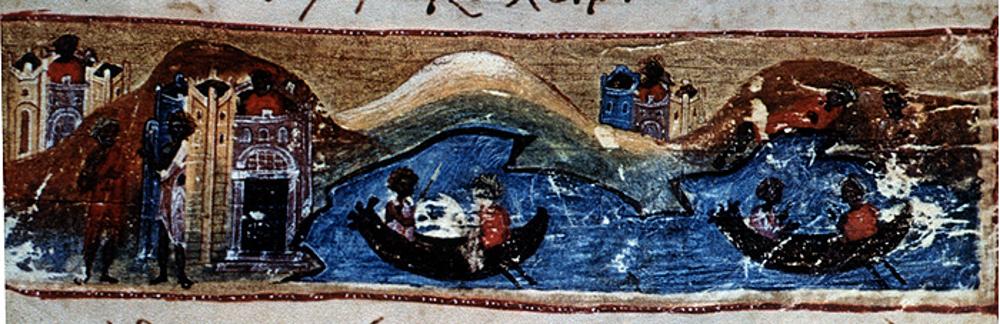

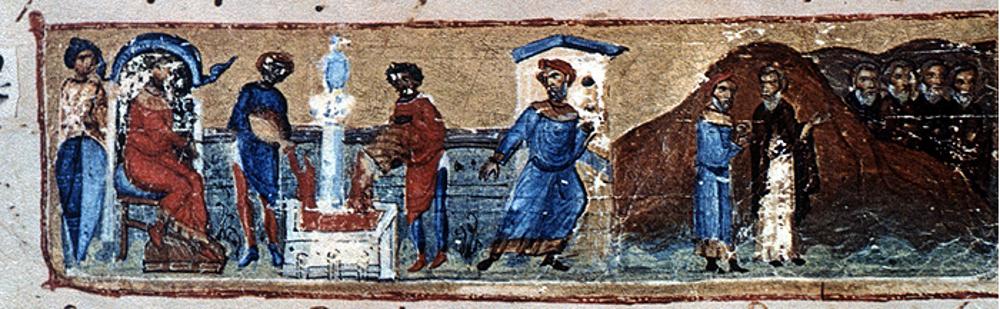

Folio 4v: King Abenner at Court, and Monks Converting the Populace

The Iveron manuscript takes the form of strips of episodes. The miniature on fol. 4v (1:5-7) introduces the main forces, whose clash gives the tale its structure. At the left the Indian king Abenner appears, like a Byzantine emperor, in a court epiphany; he then reclines for a meal attended by servants. At the right monks work to convert the king's people to Christianity. The scene of a disputation between monks and turbaned Indians is followed by one in which a monk places his hand on the head of a seated man, as a companion looks on. The miniature displays the illuminator's considerable skills. The tall figures are individually characterized in strongly three-dimensional portraits. Stylistically similar works in the Bibliothèque National, Paris (Suppl. gr. 1262), and the Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana (gr. 1927) suggest a late-eleventh- or early-twelfth-century date for the manuscript. The closest and most revealing parallel is a heavily illustrated Gospel book in the Biblioteca Laurenziana, Florence (Plut. VI.23).2 The Florence and Iveron manuscripts share conventions of author portraiture as well as extensive narrative cycles, in which the selection of consecutive pictures emphasizes dramatic action over dialogue.

The popularity of Barlaam and Ioasaph reflects a taste that led in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries to a colorful and more obviously secular literature. The rise of the so-called romance was a broad European phenomenon; it is notable that an early-thirteenth-century Frenchman added a vernacular translation in the margins of the Iveron manuscript.

J C A

1. Kazhdan J988, pp. 1187 1209.

2. Velmans 1971.

LITERATURE: Lampros 1900, p. 149; Der Nersessian 1936-37, pp. 23-25, 204, and passim, pls. I XXI; Velmans 1971; Pelekanidis et al. 1975, pp. 306-22, figs. 53-132; Kazhdan 1988, pp. 1187-1209.

Referenced as figure 115 in Arms and armour of the crusading era, 1050-1350 by Nicolle, David. 1988 edition

115A-115H Barlaam and Joasaph, Byzantine manuscript, late 12—early 13 Cents. (Iviron Monastery, Ms. 436, Mt. Athos, Greece)

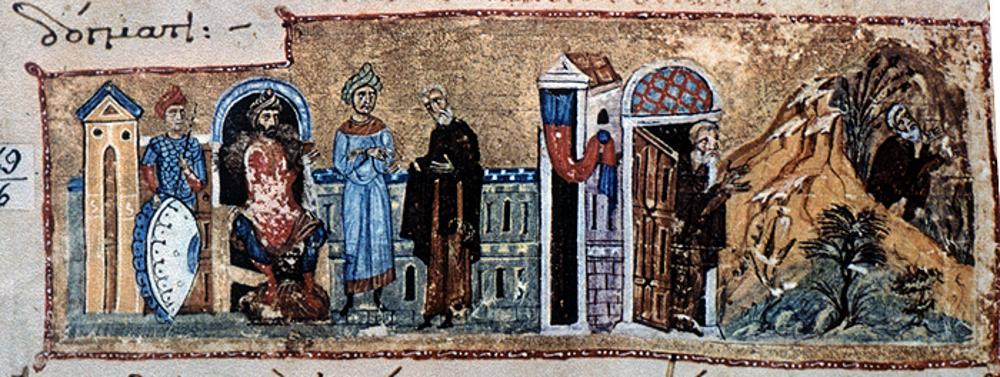

115A—f.39 “The man with three Friends”; 115B—f.4v “Guard of King Abenner”; 115C—f.5v “Persecutions of Christians”; 115D—f.114 “Guard of King Joasaph”; 115E—f.62v “Guard of the King”; 115F—f.108 “Guard of King Abenner”; 115G—f.7 “Guard of the King”; 115H—f.6 “Sacrifice to the idols”.

This manuscript contains an interesting mixture of arms and armours, some clearly realistic like the full-length mail hauberks (115A), others apparently archaized (115B and 115G). Some are a mixture of the two (115D) with a full length hauberk having incongruous pendant upper-arm protections. The mace given to the turbaned figure (115E) is a weapon conventionally given to Arabs in Byzantine art (Figs. 86B and 86J).