Amazon Audible Gift Memberships

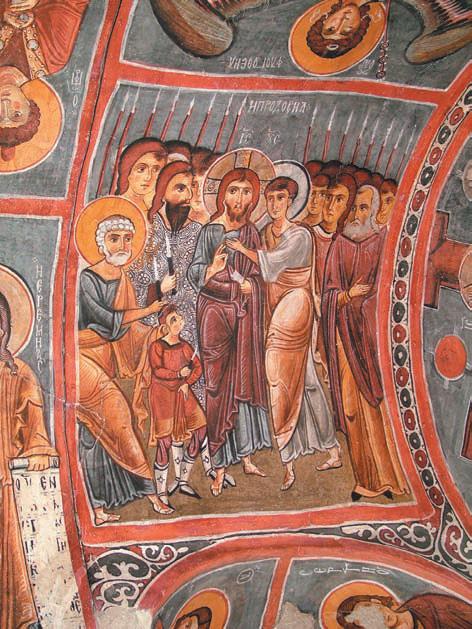

Fig. 13. The Betrayal, Qaranlek Kilissť Church, Cappadocia, mid-second half of the 11th c., authorís photo [Karanlık Kilise or the Dark Church] |

Fig. 14. The Betrayal, Email Kilissť Church, Cappadocia, mid-second half of the 11th c., authorís photo [Elmali Kilise or the Apple Church] |

Fig. 15. The Betrayal, Tcharekle Kilissť Church, Cappadocia, mid-second half of the 11th c., authorís photo [«arıklı Kilise or the Church with Sandals] |