Barlaam and Joasaph

|

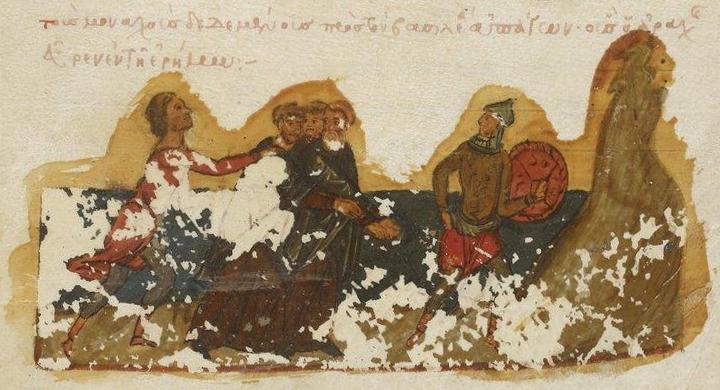

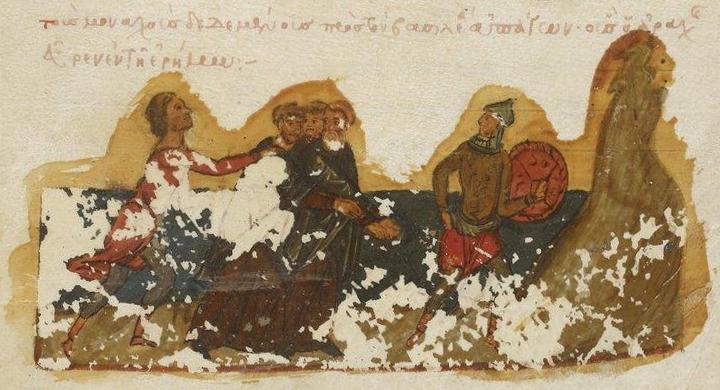

f.116v Monks taken before the King

A larger image of Monks taken before the King, Barlaam and Joasaph, Byzantine, BnF Ms Grec. 1128.

Barlaam and Joasaph

|

Titre : Grec 1128

Date d'édition : 1301-1400

Type : manuscrit

Langue : Grec

Format : Parchemin. - 203 fol. - Peint. - Petit format Parchment. - 203 folios - Painted. - Small size

Source : Bibliothèque nationale de France, Département des manuscrits, Grec 1128

Description : JOANNES S. Sabæ monachus. Historia Barlaami monachi et Joasaphi, Indiæ regis

JOHN St. Sabas, monk. History of Barlaam, the monk, and Raphael, the king of India.

Description : Barlaami et Joasaphi historia, auctore Joanne, S. Sabæ monacho

Story of Barlaam and Raphael, the author is John, a monk of St. Sabas

Referenced as figure 655 in The military technology of classical Islam by D Nicolle

655A and 655B. Manuscript, A - "Persecution of Christians," B - "Monks taken before the King," Barlaam and Joasaph, 14th century AD, Byzantine, Bib. Nat., Ms Grec. 1128, ff. 4v and 116v, Paris (Ners B).

Barlaam and Ioasaph tells a fascinating story set in an exotic land. At some time during the early centuries of the Christian Church the pagan king of India, Abenner, undertakes to rid his kingdom of Christians. He isolates his only child, Ioasaph, to shield the boy from Christianity and from all earthly concerns. Eventually Ioasaph is released, but he is confronted by sickness and poverty. Responding to divine inspiration, Barlaam, a seventy-year-old monk, travels from his native Egypt and, disguised in secular clothing, gains entrance to the palace and to the prince, converting and baptizing him after a series of conversations. Finally reconciled to his son’s faith, Abenner divides his kingdom into two parts; that which he has allocated to his son flourishes while his own falls into decline. Grasping the significance of the disparity, the king is converted to Christianity, then dies. Ioasaph renounces the throne to join Barlaam in the wilderness.

We do not know who wrote Barlaam and loasaph. It was not John of Damascus, with whom it has often been associated since the Middle Ages. Evidence points to the text’s creation in the early ninth century in Palestine, probably in the milieu of the Great Lavra of Saint Sabas. For Christian monks living in Muslim Palestine the story would have given shape to their hopes for the conversion of the caliph - following, as it does, a pattern known from medieval chronicles in which a non-Christian ruler converts and leads in the baptism of his people. The story of Barlaam and Ioasaph, in which elements of the life of the Buddha have been recognized, was immensely popular throughout the Middle Ages. At least 140 copies of the text in Greek are known, and of them 6 are extensively illustrated.

p241 The glory of Byzantium : art and culture of the Middle Byzantine era, A.D. 843-1261 edited by Helen C. Evans and William D. Wixom. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.