Ivory casket

- Title/name: Ivory casket

- Production place: Istanbul (Constantinople) (?), Turkey

- Date / period: Tenth century

- Materials and techniques: Ivory; sculpted plates, metallic tenons (formerly small ivory tenons)

- Dimensions: L. 26.4cm; H. 13.4cm; W. 13cm

- Conservation town: Troyes

- Conservation place: Cathedral treasury

The ivory casket in the treasury of the Cathedral of Troyes appears to have been brought by Jean Langlois, bishop of the city, after the sack of Constantinople in 1204.

It testifies to a period of confrontation between the Western world and the Byzantine Empire at the time of the Crusades.

The decoration of the casket provides outstanding evidence of both direct and indirect contact between Byzantium and China,

and is an excellent example of how imperial ideology was materialised in artistic production.

The casket is made of sculpted ivory plates secured together, formerly by small ivory tenons, today replaced by small pieces of metal.

It dates from the tenth century, like practically all the other Byzantine ivory pieces that have survived until the present.

This dating seems to be confirmed by the similarity of the portraits of the two horsemen to that of the emperor featured on

a panel in the Cabinet des Médailles in Paris[1].

The lid features two armed emperors on richly adorned horses.

They stand on either side of a town and are practically symmetrical.

The sovereigns wear the imperial crown with prependoulia, (with pendants), a breastplate and a spear; their

capes billow in the wind in opposite directions. People in the city buildings acclaim them.

A figure of a tyche, the personification of a city, stands in a doorway, seemingly offering a crown to the emperor at the right.

This scene depicts an adventus, a triumphant arrival in a city. Despite the positions of the emperors, they must not be thought of as leaving the city.

They are shown in hieratic frontal poses. The image, therefore, is not an illustration of what might have happened, but portrays a more symbolic dimension of the scene.

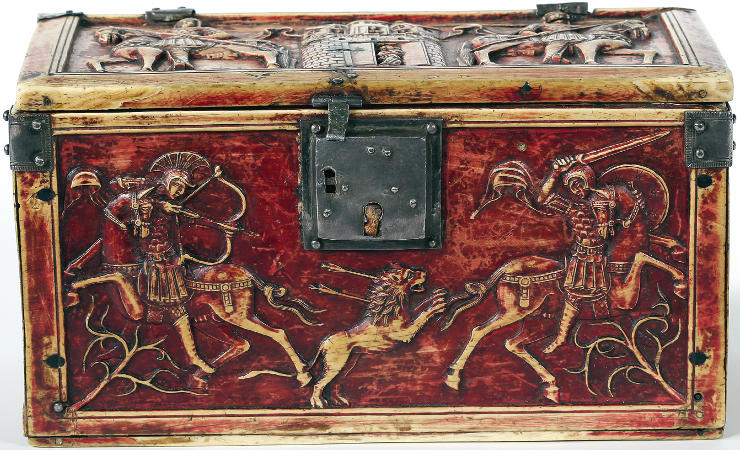

The front and rear panels both depict hunting scenes. The first shows a lion hunt.

Two symmetrically placed horse riders, one bearing a bow and the other, a sword, confront the animal.

The style of the portraits obviously alludes to the emperors on the lid. The individual on the left wears a toupha[2].

On the rear panel, a single individual, accompanied by dogs, attacks a boar using a lance. Here too the individual bears military equipment.

These hunting scenes have a strong symbolic connotation, shared by many cultures.

Hunting is more than a sport or a means of subsistence: it is a combat and thus shares its values with military crafts.

In these portrayals, hunting symbolises war, and the victory over the animal represents the triumph of the emperor.

Hunting is an affirmation of the emperor's hold over nature and the world.

This idea of domination over nature is also associated, in Byzantine panegyrics, with the gardens and parks created by emperors, where the hunts took place.

The description of the gardens and plants is used as a metaphor for the growth of the empire.

An iconographic parallel to these metaphors is to be seen on the lateral panels of the casket of the treasury of the Cathedral of Troyes,

with two birds in the midst of luxuriant growth. They are probably phoenixes, a symbol which would bolster the idea of renewal.

The artist's use of these birds is comparable to motifs from the Far East, where such birds are to be found on seventh-century Chinese plates and mirrors.

These motifs may have reached the Byzantine world through Islamic intermediaries.

Whatever the case may be, our interpretations should remain cautious given the small number of profane Byzantine objects of art that have survived until the present day.

NOTE

[1]

This panel represents Christ blessing or crowning an imperial couple. According to the inscriptions, they are Romanus and Eudoxia.

It can be dated to between 945, when the future emperor Romanus II (959-963) became co-emperor with his father, Constantine VII, and 949, the year when Eudoxia died.

[2] Crested helmet worn by emperors for ceremonies of the triumph.

Text Source: Qantara

Referenced as figure 223 in The military technology of classical Islam by D Nicolle

223. Ivory box, 11th century AD, Byzantine, Cathedral Treasury, Troyes (Ric B).

Referenced as figure 96 in Arms and armour of the crusading era, 1050-1350 by Nicolle, David. 1988 edition

96A-96D Carved ivory box, Byzantine, 11 Cent. (Cathedral Treasury, Troyes, France)

These figures probably represent ceremonial armour worn by the Byzantine Emperor and his immediate guards.

If such is the case, then these armours were very archaic and must have been designed to emphasize Byzantium’s image of itself as a continuation of the Roman Empire rather than to provide effective personal protection.