|

|

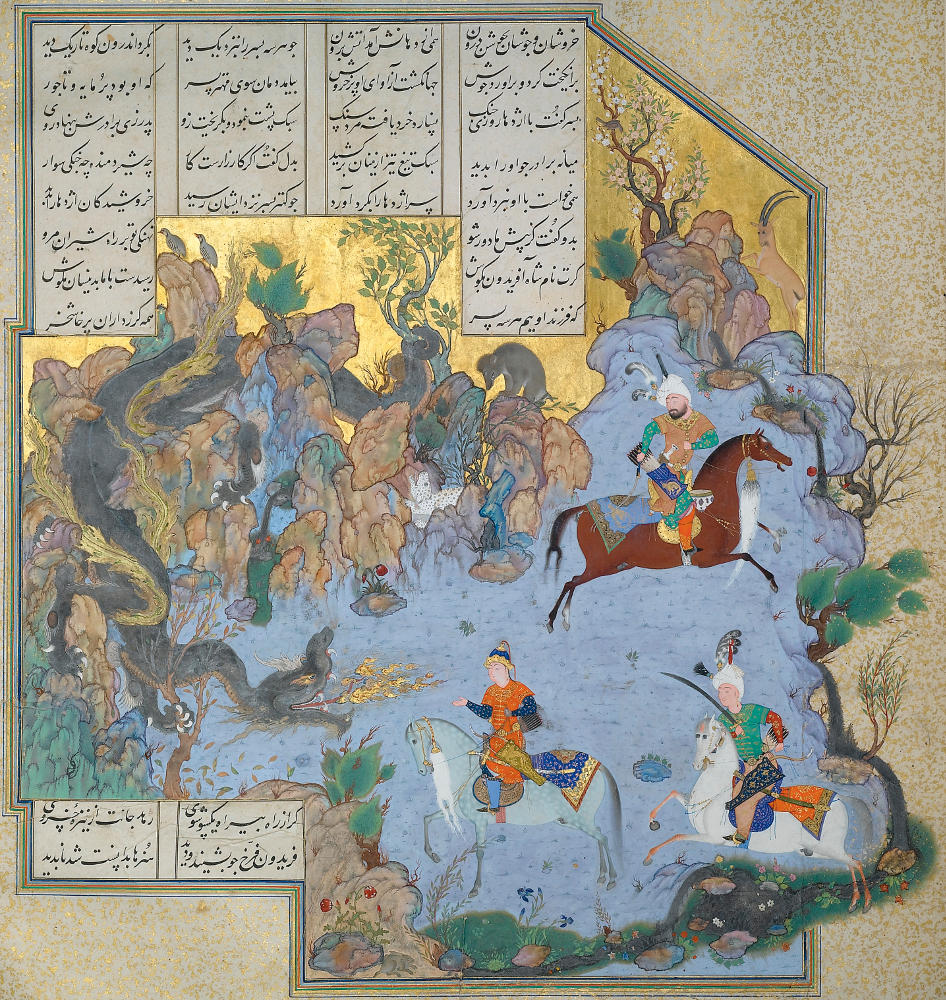

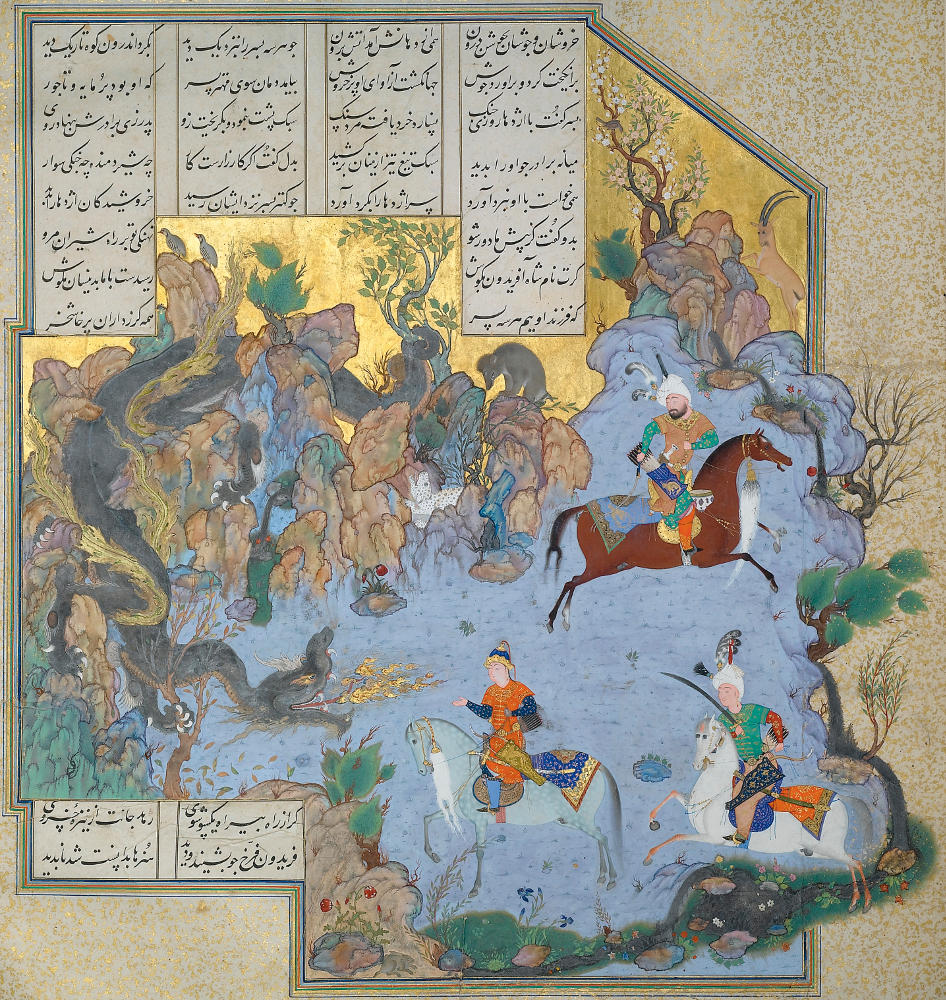

Illustration from the Shahnama of Shah Tahmasp I

f42v: Faridun Tests his Sons.

The figures wear early 16th century Persian dress.

A larger image of Faridun Tests his Sons, from the Shahnama of Shah Tahmasp

FARIDUN IN THE GUISE OF A DRAGON TESTS HIS SONS: ILLUSTRATED FOLIO (F.42) FROM THE SHAHNAMEH OF SHAH TAHMASP, ATTRIBUTED TO AQA MIRAK, PERSIA, TABRIZ, ROYAL ATELIER, CIRCA 1525-35

Estimate 2,000,000 — 3,000,000 GBP LOT SOLD. 7,433,250 GBP

Ink, opaque watercolour and gold on paper, text written in four columns of fine nasta'liq script, double intercolumnar rules in gold, wide gold-sprinkled margins, catchword at lower left corner; recto with a full page of nasta'liq text written in four columns and two headings written in white thuluth script within panels of fine illumination

Folio 47.2 by 32cm. (18 5/8 by 12 5/8 in.) Miniature: 29.7 by 28.5cm. (11 5/8 by 11¼in.)

PROVENANCE

Commissioned by the Safavid Emperor Shah Isma`il, circa 1522

Completed under the patronage of his son Shah Tahmasp at the royal atelier, Tabriz, circa 1525-1540

Presented in 1568 by Shah Tahmasp to the Ottoman Sultan Selim II

In the collection of Baron Edmund de Rothschild, Paris, 1903-1934

By Descent to Baron Maurice de Rothschild, Paris, 1934-1957

His estate 1957-1959

Arthur A. Houghton Jr., USA, 1959-1977

Agnews, London, 1977

the episode illustrated on folio 42V

The scene depicted on the present folio occurs during the reign of the legendary king Faridun. The following descriptions and translations are taken from Welch 1972, p.120, and Dickson and Welch 1981, vol.2, no.29. "Upon the death of Zahhak, Faridun reigned supreme, dispensing justice by binding evil hands with kindness. Mankind turned once again to God, and the world became a paradise. After fifty years Faridun had three sons, tall as cypresses, swift and powerful as elephants, and with cheeks like spring. In his love for them Faridun refused to tempt fate by assigning them names. When they came of marriageable age, he sought them suitable wives. Through the services of an emissary, he discovered three pearl-like princesses, daughters of King Sarv of Yemen. The nameless sons journeyed to Yemen, married the girls, and brought them home. They were met by a dragon: Faridun in disguise" "News came of their return: without delay

King Feraydun set out to block their way.

He longed to know their hearts, and by a test

Lay all his mind's anxieties to rest.

He took a dragon's form, one so immense

you'd say a lion would have no defence

Against its strength; and from its jaws there came

A roaring river of incessant flame.

He saw his sons; dust rose into the sky,

The world re-echoed with his grisly cry.

First he attacked the eldest prince, who said,

"No wise man fights with dragon foes", and fled.

Seeing his second son, he wheeled around.

The youth bent back his bow and stood his ground,

Shouting, "If combat's needed I can fight

A roaring lion or an armoured knight."

Lastly the youngest son approached and cried,

"Out of our path, fell monster, step aside.

If you have heard of Feraydun, then know

That we're his valiant, lion-like sons, now go,

Or I'll give you a crown that you'll regret!"

He saw how each son took the test he's set

And disappeared. He left them there, but then

Came out to greet his princes once again-

Their king now, and the father whom they knew,

Surrounded by his royal retinue."

the artist

Aqa Mirak was one of the leading royal artists of Shah Tahmasp's reign and is thought to have been the director of the atelier during the later years of the production of this manuscript. Many of the illustrations in his crisp, clear style, with a vibrant palette and relatively large figures, are to be found in the later pages of the Shahnameh. He was a man of diverse abilities who, in addition to his work as an illustrator of manuscripts, devoted time to the decoration of mosques and palaces. He had special skills as a colourist and preparer of pigments, skills which can be seen to have contributed to the peculiar lightness and clarity of his miniatures. He was a close companion of Shah Tahmasp himself and contemporary sources indicate how highly he was regarded by his fellow artists. Welch gives a lengthy and perceptive account of Aqa Mirak in volume I of the 1981 publication The Houghton Shahnameh (pp.95-117). Therein we discover that Dust Muhammad, another of the artists of the royal atelier, describes Aqa Mirak thus: "the surety of the community of Sayyids, the genius of the age, the prodigy of our era.....the Heir to the Khans....among those privileged to approach the Shah....At the House of Painting he but picks up his brush and depicts for us pictures of unparalleled delight. As for likenesses - and where are their like? – as the farseeing view them, they are foremost in sight. God grant him his pictures and paintings! Good Lord! The glory of this painter! What God-given might!"

(Dickson and Welch, Vol.I, p.95) Sam Mirza, another of his contemporaries, describes him as "a genius of the age, as peerless in designing as in painting.....the guiding spirit of the corps [of artists]." (ibid. p.95). Finally, Qutb al-Din, writing in 1556-7, describes him as "the peerless paragon for the host of means and the myriad modes employed in this art...". Welch suggests that such was his reputation amongst his fellow artists and his patron that he was given the honour of painting the first illustration in this copy of the Shahnameh, the scene of Firdausi and the Court Poets of Ghazna, on folio 7, and some of his most dramatic and fully expressed works appear in the first part of the manuscript, including the present painting (folio 42). Welch suggests that although these two folios illustrate early episodes in the Shahnameh, they are works of Aqa Mirak's mature phase, and he compares their style and execution with the artist's work for the royal copy of the Khamseh of Nizami of 1539-43 (British Library, Or. 2265). Aqa Mirak's career continued after the decline of Shah Tahmasp's interest in painting in the 1550s, and he subsequently painted for Prince Ibrahim Mirza. In his discussion of Aqa Mirak, Welch described the present illustration of Faridun in the Guise of a Dragon Tests His Sons as follows:

"The style of Aqa Mirak's last picture for the Shahnameh, Faridun, in the Guise of a Dragon, Tests His Sons, is identical to that of his work in the Nizami of 1539-43. More subdued in palette than his other pictures for the Houghton manuscript, it suggests dusk, or an overcast day. Having overcome all technical problems as well as his own inhibitions, the artist could tell his story more directly, to greater effect, and with livelier expressiveness. He had learned that he could understate. Although earlier Aqa Mirak could not always hold our interest, even with maximum exertion, now he can captivate with a nuance. In composition, Faridun Tests His Sons is like the finest watch, possessed of the softest tick and the least evident works; we barely sense the sinews and muscles that bind the picture together. Although the master has set himself a forbidding task, we are no longer perturbed by the strain of his thought. The dragon's springing silver, black and gold body is echoed by the delicately sinuous cascade, which broadens into a stream as it falls and ultimately leads us back into the foreground, terminating at the feet of the cringing rabbit. Thus, our eye pursues a continuous circle of delight, from stream to dragon and round again. Spatially, too, Aqa Mirak has achieved mastery. Foreground and background are clearly demarcated, even though the work is free of illusionism. We have met Faridun's three sons elsewhere:.... The painter has infused all three faces with personality – they seem portraits rather than types. The faces in the rocks are psychologically interesting, rivalling or even surpassing Sultan Muhammad, and suggesting that this picture is Aqa Mirak's reply to the great Gayumars."

(Dickson and Welch 1981, vol.I, p.108)

Source: Sothebys

In order to decide the division of his kingdom, the good king Faridun put his three sons to the test by appearing to them in the guise of a terrifying dragon.

To Salm, named for his prudence in the face of danger, he gave Rum and the West (the Byzantine Roman Empire).

To Tur, “whose bravery shines brighter than flames” he gave Turan and China (Central Asia and the Chinese Orient).

To his youngest son Iraj, who came up with a sensible solution faced with the dragon, proving that he was the most worthy of all of them, he bequeathed his crown and the kingdom at the centre of the world, Iran and the Arab territories.

Iraj’s two older brothers were jealous and plotted to kill him, threatening war if Iraj did not receive a kingdom as distant as theirs.

When Iraj visited them, without an army, to make them offers of peace, Tur decapitated him.

Faridun was inconsolable, mourning the death of his favourite son and the treachery of his elder brothers.

In the years that followed he devoted his attention to the education of his grandson and heir Manuchihr.

Salm and Tur discover that Manuchihr has trained in all the arts of warfare, that he commands a powerful army and intends to avenge Iraj’s death; terrified, they send a messenger to Faridun, begging him to pardon them and promising to serve Manuchihr faithfully.

Faridun cannot trust them, replying “And we will drench with blood, both leaf and fruit, the tree sprung out of vengeance for Iraj.”

|