Find the perfect fit with Amazon Prime. Try Before You Buy.

Extracts from

The Representation of Costumes in the Reliefs of Taq-i-Bustan

Artibus Asiae, Vol. 31, No. 2/3, 1969

Elsie Holmes Peck

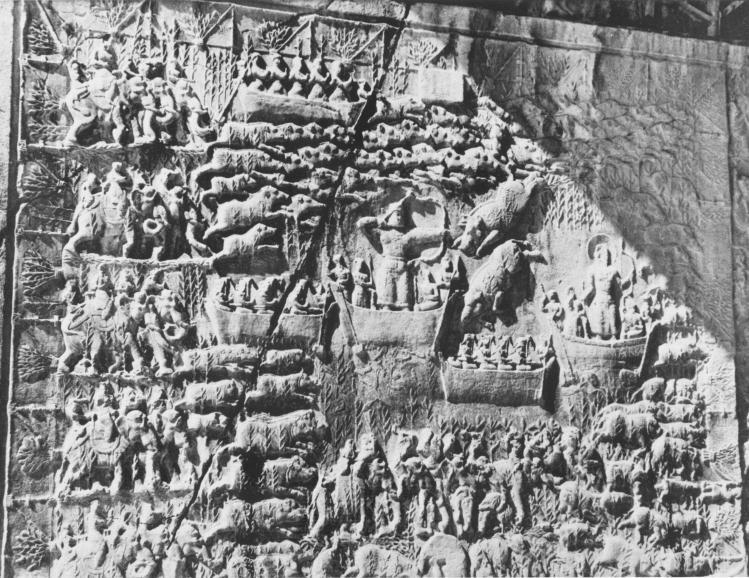

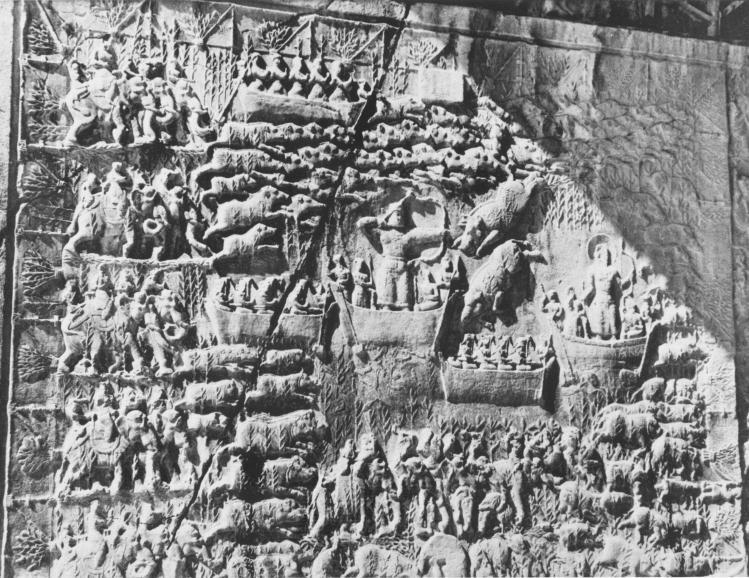

Plate III. The Boar Hunt.

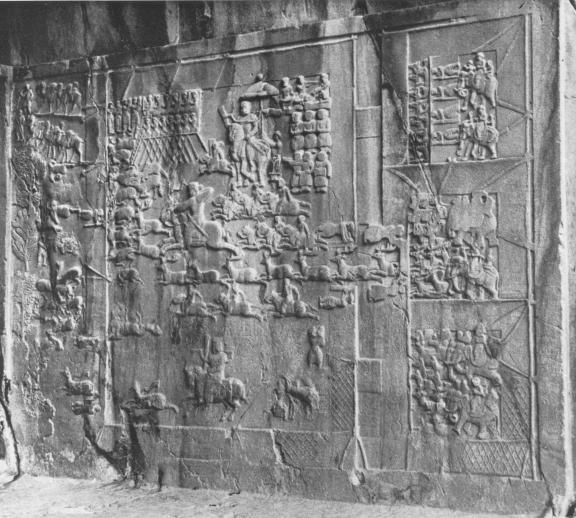

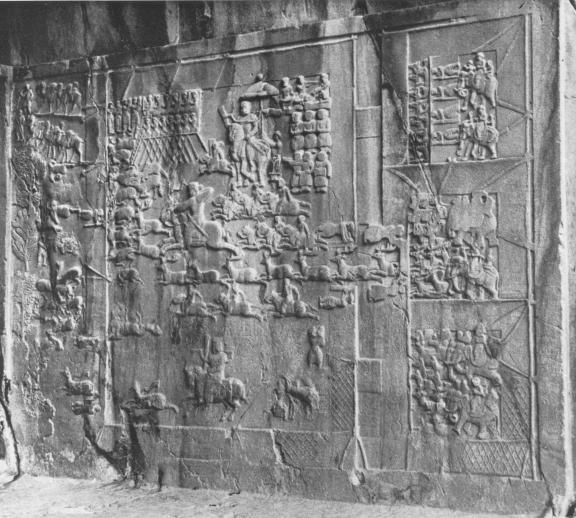

Plate V. The Stag Hunt.

THE DRESS OF THE ELEPHANT RIDERS IN THE BOAR HUNT RELIEF

In the boar hunt relief, each elephant is ridden by a large figure in the saddle. The rider’s great size and elegant, rich costume characterize him as a member of the king’s court. The smaller mahouts who guide the animal from the neck or cling to the back of the elephants, as their undecorated tunics would seem to indicate, are probably not of noble rank. In some cases their costumes consist of a long-sleeved tunic which reaches below the knee and is belted at the waist by a thick girdle from which hang four thongs (Pl. VI). High boots are worn over trousers and come to a point below the knee. The bodice of the tunic is covered with a pattern of stylized folds unlike the smooth decorated caftans of the chief riders.

All the mahouts wear trousers and high boots and the majority are clad in what appears to be a short tunic or one that is rolled up above the knees. An over-skirt is gathered up on the sides and tucked into and over the belt to allow for greater freedom of movement (Pl. VII). Here too, the garment seems to be of a light, soft material that falls easily into folds.

104

...

THE ROBES OF THE RIDER-COURTIERS

IN THE BOAR AND STAG HUNT RELIEFS

Turning from the female garments of the harpists to a discussion of costumes worn by men in the hunting reliefs, one notices at once that the entire surface of the robe is covered with patterns. The chief riders, nobles of the court, wear sumptuous, tight-fitting, long-sleeved garments belted at the waist. Leggings or baggy trousers appear below the caftan and these too are embellished with designs (Pls. VI, XII). The rider-courtier on the first elephant in the second row from the top in the boar hunt relief wears a robe which is similar in shape to that worn by a secondary mahout (Pl. XII vs. Pl. VI). The skirt reaches below the knee, dipping down slightly in front. The irregular hem line is not repeated on the costume of the other elephant riders.

The remaining nobles on animals in the boar and stag hunt reliefs are clad in skirts which have a very characteristic contour. The robe reaches to above the knee and then drops down on the side in two narrow scallops (Pl. VI). The silhouette is emphasised by the broad decorated border which follows the edge of the skirt.

There are several explanations for the curious outline of the hem. Either the skirt was drawn up underneath to raise the sides in order to make the garment more suitable for riding, or the complex hem line may simply indicate a popular fashion for this type of skirt. The former explanation is possible since the Parthians wore a short tunic gathered up at the sides50. Henri Seyrig describes the Parthian costume of the first half of the second century A.D., thus: La tunique parthe est une simple blouse … qui forme par devant et par derrière une sorte de tablier arrondi, soit par une coupe

110

Appropriée, soit qu’elle fut troussée sur ses coutures laterals … Elle doit répondre à la forme analogue que l’on observe sur les reliefs sassanides de Ia seconde période, comme à Taq-i-Bustan51.

It would seem, then, that this particular type of garment was adopted by the Sasanians. On the relief of the Investiture of Ardeshir II of the fourth century A.D. at Taq-i-Bustan, the king is clad in a tunic which seems to be gathered up at the sides thus producing a round apron effect in front (Fig. 7)52. Similar garments appear to be popular from the fourth to seventh centuries A.D.53. They continue in use into the eighth century A.D. where a representation of the garment is found in the Umayyad remains of Qasr el-Heir el-Gharbi. Fragments of a stucco statue of a prince show the figure clad in a tunic, the skirt drawn up at the sides54. Schlumberger describes the outline of the skirt as formed by belts lifting the hem on the sides at the hips55.

One cannot deny the possibility then, that the elaborate contour of the riders skirt could be due to some device which raised the side of the garment. Nevertheless the second explanation seems more likely, that at this period fashion veered toward more complex skirts and hem lines.

In the Parthian period, by the third century A.D. a trend which was increasingly popular in Palmyra led to skirts which dipped down sharply at the side to form points (Fig. 8)56.

Even the art of Gandhara in the third and fourth centuries A.D. was influenced by this Parthian fashion57. The skirts of the rider-courtiers in the hunting reliefs dip down at the sides, rise and dip again to form two narrow scallops. Although the Palmyrene skirts are not as complex in outline as those at Taq-i-Bustan, and although they are more sharply pointed, the general effect of skirts dropping down at the sides is not dissimilar.

In the Sasanian period skirts with dipping hems became popular only toward the end of the dynasty58. All representations of the garment are found on vessels dated either to the time of Khusrau I or later. The cup of Khusrau I of the sixth century A.D. in the Bibliothèque Nationale shows the enthroned ruler clad in a garment not unlike those worn by the elephant riders at Taq-i-Bustan (fig. 9)59. Here too the robe is long-sleeved, tight-fitting and embroidered with patterns. The edge of the skirt is also adorned by a wide decorated border and the hem dips sharply on both sides. An oval vessel in the Walters Gallery dated by Ghirshman to the sixth to seventh centuries A.D., depicts a figure to the left of the king wearing a garment which hangs down on the sides in points, the edge of the skirt defined by a patterned band60. Very similar to the elephant rider’s costumes and their contours is the robe with a wide border worn by the king on the Tcherdyne plate in the Hermitage Museum and dating from the same period (fig. 10)61.

The ruler’s costume is not seen from a completely frontal view so that one notices that after

111

initially dipping down on the side in a sharp point, the hem rises in a semi-circle to drop again before rising a second time in the back. This is in fact the same outline created by the skirts of the courtiers in the boar hunt relief, although there the points of the skirt are not sharp.

Finally, the closest parallel to the costume worn by the nobles riding elephants is found on a plate of the sixth century A.D. in the Hermitage Museum depicting Khusrau I enthroned with officials of his court62. The nobles wear a robe which forms an arc in front and drops down near the sides but rises again immediately (Fig. 11). The lowest points of the garment, as shown by the contour of the border, are not pointed but rounded thereby relating the costumes of this plate in the Hermitage Museum very closely to the garments worn by the chief elephant riders at Taq-i-Bustan.

The closest parallels for the courtiers’ robes outside of Iran, are those worn by ambassadors on the newly discovered wall paintings at Afrasiab in ancient Samarkand63. These wall paintings, dated to the seventh century A.D. by the Russian scholars depict nobles bearing gifts clad in tight fitting, embroidered caftans, the hems dipping slightly to the sides. A three-quarter view permits one to see that the contour of their skirts is identical to that of the ruler on the Tcherdyne plate. We shall find in the course of this paper several points in common between these Central Asian wall decorations and the reliefs of Taq-i-Bustan (cf. below pp. 115, 118).

This type of costume then, would appear to have been adopted as a fashion only in the closing century before the fall of the dynasty and at the same period or slightly later in Central Asia. The late appearance of the garment would tend to justify a late date for the reliefs of the boar and stag hunts.

THE LEGGINGS OF THE ELEPHANT RIDERS

IN THE BOAR HUNT RELIEF

The nobles riding elephants wear under their robes either full trousers which extend down over a small shoe, or a more complex arrangement (Pl. XII). The latter probably consists of a separate piece of stiff material over the trousers rising up to a point near the knee and reaching down to below the calf (Pl. VI). The attachment is not visible. This legging is covered by a variety of animal or floral designs. The less important mahouts wear a simple high boot which also comes up to a point below the knee (Pls. VI, VII). These two types of leg covering are often difficult to differentiate, particularly on later Central Asian cave paintings.

During the Parthian period in the second century A.D., funerary reliefs from Palmyra show figures clad in loose leggings over trousers. Seyrig describes this garment as a long tube of leather or material attached by a cord to a hidden belt64. The legging is admirably suited to peoples who spend much of their time on horseback, and would probably have been a Parthian importation from their nomadic days. It dies out in Palmyra by the middle of the second century A.D.65.

112

Seyrig traces the legging into the Sasanian period. He believes that the fluttering, billowing trousers of the early Sasanian kings are in reality leggings which are attached by a ribbon under the tunic to an unseen belt66. The reliefs of Shapur I in the third century A.D. at Bishapur and Naqsh-i-Rijab bear out the theory67. A post-Sasanian hunting plate in Leningrad of the seventh to eighth centuries A.D. provides a later example. The ruler wears decorated leggings drawn over trousers of another material, the attachments disappearing under the tunic68. The particular fashion remains popular for a long time, and is depicted on buff ware painted pottery of the ninth to tenth centuries A.D. from Nishapur in northwest Iran69.

Even farther east, in Central Asia, the leg-covering is worn by donors in wall paintings of the seventh century A.D. at Ming Oī, Qyzil (Fig. 12). In the cave of the Sixteen Sword-bearers, rows of donors wear leggings under their caftans and over full trousers70.

BOOTS WORN BY THE MAHOUTS IN THE BOAR HUNT RELIEF

In the boar hunt relief, the mahouts guiding the elephants at the neck and goading them behind wear high simple boots with a pointed front rising to the knee (Pls. VI, VII). This foot-gear is related even more closely to Central Asian representations than the leggings worn by the rider-courtiers. Kneeling donors from frescoes at Bezeklik of the eighth century A.D. wear high boots which rise in the front to a point just below the knee (Fig. 13)71. Beneath the top, the boot has a circular hole from which emerges a cord which then disappears under the tunic where it is probably attached to a belt worn under the garment72. The outline of the boots is akin to that worn by mahouts at Taq-i-Bustan. A statue of a seated noble of the sixth to seventh centuries A.D. from Fondukistan is shown with similar boots. Here they seem to be made of supple leather, the pointed front of the boot becoming elongated to form a band which in turn is hidden under the skirt but is presumably attached to an inner belt73.

The boots of the mahouts in the boar hunt relief, however, lack any attachments to a hidden belt. Closer parallels to these boots are also seen on Central Asian frescoes. Although a great many representations of these boots come from wall paintings contemporary or slightly later in date than Taq-i-Bustan, their frequent appearances in Central Asian cave paintings would seem to indicate that these boots were in use over a longer period of time than the early seventh to eighth

113

centuries A.D. The fashion for boots had already traveled as far as China by the sixth century A.D. and is seen on a Northern Ch’i platform in the Freer Gallery in Washington, D.C.74 On the stone relief where influence from Iran, India and Central Asia are found side by side, the guardians standing on lions and the tiny musicians in pearl roundels wear Central Asian boots. Tall heavy boots were undoubtedly introduced into Central Asia and Afghanistan by tribal peoples to the north who came down and settled in these regions. Kushan rulers of the second century A.D. are shown in statues with thick padded boots which may be an indication of the nomadic origins of the dynasty (Fig. 14)75. By the seventh century A.D. these boots begin to make an appearance on Central Asian wall paintings and panels. Votive tablets from Dandan Olug (Khotan) of this date show men seated or riding wearing high boots76 and at Ming Oī, near Qyzil, donors and warriors alike are represented wearing elegant black and blue boots77.

The fashion for this type of foot-gear did not become popular in Sasanian Iran until the sixth century A.D. during the reign of Khusrau I. The boot is always high, the top rising to a point and the surface often decorated with patterns. The officers of Khusrau I on the plate in the Hermitage Museum wear these boots as does the king in the slightly later Tcherdyne plate and the figures on the oval dish in the Walters Gallery of the same period (Figs. 10, 11)78. A plate in the Walters Gallery representing a Royal Feast appears slightly later in date due to the style of rendering the figures79. The king is shown clad in high boots, the surface covered by floral scrolls (Fig. 6b). Indeed, high boots were still in use well after the Islamic conquest and so can be seen on post Sasanian vessels of the seventh to ninth centuries A.D.80

In summary it may be said that the leggings and boots worn by the mahouts in the hunting reliefs are fashions originally derived from nomadic peoples whose life on horseback would force them to develop appropriate foot-gear. These tribal groups from the steppes of Asia later settled in Parthian Iran and Central Asia. In Sasanian times the high boot was not introduced before the sixth century A.D., after which date it because increasingly popular and was carried on after the fall of the empire. The late appearance of leggings and boots on silver vessels would tend to strengthen the argument for a late dating of Taq-i-Bustan.

THE ROBES OF THE KING AND HIS COURTIERS

IN THE BOAR HUNT RELIEF

An analysis must now be made of the garments worn by the king and other members of his retinue. In the boar hunt relief, the ruler and his nobles in the royal boat and the courtiers clapping

114

in the boat above, all wear tight-fitting, stiff robes with long skirts reaching to mid-calf which we call caftans. The sides of the boats hide part of the figures so that one cannot tell if the nobles would have been clad in trousers, boots or leggings. Only a small section of the king’s embroidered trousers can be seen (Pl. XIII). The collars of these robes are high and the cuffs are wide and embroidered. These caftans are heavily embellished with precious stones and intricate patterns and are circled at the waist by wide jewelled belts (Pls. XIV, XV, XVI, XVII, XVIII).

The caftans appear to be made of a stiff, heavy cloth which encases the body closely and does not readily fall into folds. Clément Huart describes the winter dress of the Sasanians as being “garments of silk or wool padded with coarse silk stuffing” for warmth81. If this were indeed the case, it would account for the unyielding quality of the material.

The king’s garment will be discussed first since the royal caftan differs from those of the nobles for it seems to be fastened down the front as a coat (Pls. XIV, XIX). Perhaps a prototype for the garment may be found in the statue of Kanishka of the mid second century A.D. from Mathura (Fig. 14)82. The Kushan ruler is shown wearing a long coat, open down the front displaying a shorter robe underneath. The coat is of a heavy felt or leather and if it were closed, the effect would not be unlike that of the royal caftan of Taq-i-Bustan. The stiff coat garment is seen throughout Central Asia on cave paintings. Donors of the seventh century A.D. cave of the Sixteen Sword-bearers at Ming Oī, Qyzil, are clad in caftans which fasten down the center (Fig. 12)83. Here too the robes are of rigid cloth, but open in front, with a broad lapel. An earlier painting at Bamiyan of the fifth to sixth centuries A.D. shows a slight variation of the garment in the robe worn by a Sun deity84.

The robes worn by the nobles are related to the caftan for they too are close-fitting and are of a heavy material. They are not closed at the front of the dress and it is difficult to see how they would have been fastened (Pls. XV, XVI, XVII, XVIII). Caftans similar to those of Taq-i-Bustan are found in Central Asia on wall paintings of the seventh century A.D. at Pyanjikent (Fig. 15). Here nobles participating in a ritual feast wear tight-fitting caftans whose long sleeves and wide embroidered cuffs are akin to the garments in the boar hunt relief85. The wall paintings at Afrasiab of the same date show ambassadors also clad in long robes of stiff material, heavily embroidered with wide cuffs and borders at the hem86. In India proper, the caftan was also fashionable, and the frescoes depicting the Mahajanaka Jataka in Cave I at Ajanta of the sixth to seventh centuries A.D. represent Mahajanaka clad in such a robe87. Its long tight sleeves and decorated surfaces relate it to the robes of the boar hunt relief.

The caftan, which has travelled west from India, Central Asia and Afghanistan, is found on wall paintings to the west of Iran at Samarra in the ninth century A.D. and in eastern Iran at

115

Nishapur where it is seen in painted pottery designs of the ninth to tenth centuries A.D.88 The rigid outline, embroidered surfaces, and close fitting silhouette are retained in Post-Sasanian times. A similar garment is found at the beginning of the ninth century A.D. in Afghanistan at the Ghaznavid palace of Lashkari Bazar89. The Audience Hall is covered by murals depicting male figures, possibly the guard of the Sultan, wearing long caftans with narrow sleeves. The bodice of the robe is open with lapel which, if closed, would probably fasten on the shoulder. Schlumberger, discussing the garment, relates it to the robes of Taq-i-Bustan by saying that if the caftans of the boar hunt relief have no lapels it is simply because they are closed90.

THE SHOULDER DECORATION AND THE COLLARS

OF THE CAFTANS IN THE BOAR HUNT RELIEF

The robes of the nobles in the boar hunt relief are decorated in an unusua1 manner. The shoulders of many of the robes are embellished by rectangles of heavily embroidered material which are reminiscent of epaulettes (Pls. XV, XVI). On the other hand it is possible that the decoration represents the fastening of the robe. The practice of decorating the shoulders of the garments by medallions and other designs is not uncommon. Coptic tunics from Egypt of the fifth century A.D. are often adorned in this fashion91, as are the tunics of figures in the fifth century A.D. mosaics from Antioch92.

Turning from the West to Iran we find that this practice occurs often on the undecorated filmy draperies of the kings in Sasanian metalwork)93. Here the shoulder decoration usually consists of rosettes set in roundels,

The closest parallel to the shoulder decoration on the boar hunt relief comes neither from the West nor from Sasanian Iran. The nobles of the seventh century A.D. paintings at Pyanjikent wear robes which are adorned at the shoulders by two long epaulettes covered with rosette patterns (Fig. 15)94. The rectangular outline of the Central Asian decoration is more akin to that on the robes of the nobles in the boar hunt relief than the earlier examples from Sasanian Iran and further west.

The panel of embroidered material on the shoulder of the courtiers’ caftans at Taq-i-Bustan may possibly represent the fastening for the garment. Since the decoration appears only on the left shoulder it is probably an extra piece of cloth which covers the shoulder to conceal the fastening. We have seen that the open lapels of the caftans from Central Asia and Lashkari Bazar,

116

if closed, would probably fasten on the shoulder in the same position. A Gandharan donor figure and a devotee of the sixth century A.D. from Sahri Bahlol have curious beaded designs on the front of their garments95. Harald Ingholt in describing it says, “The beaded outline on the left breast no doubt indicates a fastening of the caftan96”. He then draws parallels with garments of the same date from reliefs of Palmyra and Dura Europos97. Although the nobles’ robes at Taq-i-Bustan do not have an exactly similar arrangement, it is reasonable to suppose that the shoulder panel is somehow related to the fastening of the garment.

A unique feature of these caftans in the boar hunt relief and one which is not seen on the Central Asian examples is the high, stiff, embroidered collar (Pls. XV, XVI, XVII, XVIII). This collar seems peculiar to Taq-i-Bustan since it is not found in other Sasanian representations. The only remotely close comparison is of the Pazyryk finds from the Altai dating from the fourth century B.C. Here, depicted on felt trappings from a tent, a goddess (?) and a rider wear high, stiff collars98.

The donors in the cave of the Sixteen Sword-bearers from Ming Oī, Qyzil, have wide lapels from which, often hang long, tongue-shaped bands of material (Fig. 12)99. It is possible that if the lapel were closed these bands could then have been wrapped round the neck and fastened, producing a high collar comparable to those of Taq-i-Bustan. Since, however, no representations of this type of dress have been found the origin of the high collar of the nobles’ robes in the boar hunt relief remains enigmatic.

The particular form of the caftan as it appears in the boar hunt relief is not repeated again in Sasanian art. It is related, nevertheless, to the garment represented on metalwork of the sixth to seventh centuries A.D.100 This robe is also of a stiff material, heavily embroidered and with long, tight sleeves. Its hem, however, invariably dips at the sides in sharp points unlike the skirts worn by the nobles and king in the Taq-i-Bustan relief. The caftan, then, would seem to be a fashion originating in Central Asia with its beginnings in the stiff coats of the formerly nomadic people, the Kushans. It was adopted in Iran only toward the end of the Sasanian period. At Taq-i-Bustan the caftan assumes a special form which seems to be unique to this site. After the fall of the dynasty the caftan becomes very popular and widespread, appearing in areas as far apart as Samarra and Afghanistan.

THE THONGED BELTS OF THE KING AND COURT

IN THE BOAR AND STAG HUNT RELIEFS

The discussion must now turn to the wide jewelled belts which encircle the waists of the caftans worn by the ruler and his nobles. The first type of belt to be analyzed, perhaps the most interesting, is the belt from which hang ornamented thongs. This girdle is worn by the king, a number of nobles in the boats, mahouts and the servant in the stag hunt relief holding the parasol (Pls. VI,

117

XII, XIII, XVI, XVII, XVIII, XIX). The servant’s belt is decorated with only a few thongs, those of the nobles and elephant riders have a greater number and the royal belt is adorned with as many as ten. The belt is closed by an ordinary buckle, while the surface of the belt is sometimes divided into tiny panels each containing what seems to be a large jewel in a round setting. Directly beneath these panels hang the stiff thongs which must be made of leather. These in turn are embellished either with round gems echoing the decoration of the belt or less elaborately by oval plaques perhaps of metal. In some cases the straps are overlaid by shorter thongs creating an even more complex pattern.

The belts with lappets are not Sasanian in origin but are imported from the East and appear on no other Sasanian representations. They abound in seventh century A.D. cave paintings from Central Asia. At Bezeklik, kneeling donors in Buddha groups from the temples are often clad in belts with hanging straps101. In Temple Nine they appear to be made of red or black leather, the lappets tipped with metal and embellished with gold scales or silver heart-shaped forms102. Here the thongs seem to have primarily a decorative function since no objects hang from them (Fig. 13). A ring suspended between the straps of the black belt is attached to a scabbard thrust into the belt. At Taq-i-Bustan, the lappets are also chiefly ornamental except on the king’s belt which has a ring suspended from a thong, which in turn carries a piece of material (P1. XIII).

A fragment of a wall painting from the entrance to the cella of Temple Nine at Bezeklik seems to emphasize the purely decorative purpose of the thongs103. A donor figure in a long robe wears a belt with short straps which are plaited and tipped with metal. Between them hang a multitude of objects all suspended by cords attached to the belt. The short thongs are not used to suspend any of the objects. On another painting from the Central Asian caves of Bezeklik straps are often more than mere decoration. A mural from the cloisters of Temple Twelve shows a girdle from which hang numerous thongs of various lengths studded with metal plaques, only the shortest being used to suspend small boxes, horns, and cloth104.

Cave paintings from other Central Asian sites also show this belt. The ambassadors on the wall paintings at Afrasiab of the seventh century A.D. are girded at the waist by belts from whose lappets hang daggers and swords105. At the same time in Cave Three A at Sorcuq106, belts are depicted on wall decorations with thongs very similar to one worn by an attendant on a painting from Astana of the seventh to eighth centuries A.D.107.

Ghirshman believes that these belts are ultimately derived from those worn by nomads, the most ancient belts found of the fifth to sixth centuries A.D. in Siberia and Mongolia108. Belts with thongs were not in use extensively until the time of Attila the Hun in the fifth century A.D. No prototypes are found as early as the fifth century A.D. in the West but by the sixth to seventh

118

centuries A.D. their appearance is more universal, spread by the migrations of the Avars)109. These belts, then, came originally from the Altai and Mongolia and were worn by the nomadic Avares and Kryluzes110, Avar tombs found in Hungary have brought to light the most complete examples of this type of belt. The upper belt of lappets was an insignia of rank designating the power and position of the owner; the lower belt was used for the purpose of suspending weapons111.

A Post-Sasanian plate in the British Museum, which Ghirshman dates in the seventh century A.D. shortly after the fall of the dynasty represents a figure in a banquet scene clad in a girdle with short straps studded with metal circles (Fig. 16)112. The stylization of the drapery and the heavy square faces of the figures are closer to Central Asian than Persian prototypes. Perhaps the plate was made on the eastern borders of Iran which would account for the presence here of a Central Asian type of belt.

In the ninth century A.D. the fashion for belts with thongs had travelled as far west as Samarra where it appears on wall paintings with only slightly decorated or overlapping straps113. In the northwest of Iran at the same period, a falconer on a wall painting from Nishapur is clad in a low belt from which hang three long thongs decorated with scales and studs of metal114. Charles Wilkinson describes it thus, “A leather belt with tails tipped and studded with metal encircles the waist and from it hang two curved swords115”. He traces this belt from Central Asia to Sasanian Iran and accounts for its appearance at Nishapur by the fact that it was originally a Sasanian city116.

A little over a century later at the Ghaznavid palace of Lashkari Bazar figures of the Turkish bodyguard of the Sultan on the walls of the Audience Hall wear girdles with long thongs reaching to the hem of the garment forming a decorative pattern on the skirt. The shorter lappets are used for the suspension of small articles, such as money bags117, Schlumberger believes that originally the belt came from Chinese Turkestan, and he accounts for its presence here by the fact that the Turkish bodyguard probably imported the fashion from Central Asia and the steppes118.

In the following century one finds the fashion still in use as represented on Islamic stucco sculpture of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries A.D.119 An actual belt from this same period is in the British Museum and consists of decorated plaques which must have been fixed to leather thongs120. Basil Gray in his article on these finds, reported to come from Nihavand, says “As

119

with other nomad peoples the belt was of considerable importance to the Turks, and was, in fact, an emblem of rank121”. It would seem at Taq-i-Bustan that the belt with thongs is indeed a symbol of power and position, for servant is clad in simple girdle while the king himself wears the most heavily ornamented and complex belt on the hunting reliefs.

In all representations of the belt with straps, the form is never rigidly symmetrical as those found on the reliefs at Taq-i-Bustan. Here the thongs are all of the same length, spaced closely together with the same number of straps hanging on each side. The static arrangement is probably due to the Sasanian love of balance and symmetry. Despite the stylistic differences, the belt itself is obviously derived from eastern prototypes. The previously held opinion that the figures surrounding the king in the boar hunt relief are members of the royal harem cannot be accepted since the belt with thongs and the caftan seem to be exclusively male garments122.

JEWELLED BELTS WORN BY NOBLES IN THE BOAR HUNT RELIEF

The other belts represented in the boar hunt relief are formed by large jewelled bands with buckles. In some cases panels of embroidered material hang over the belts and down the front of the garment as they do over the belt with thongs (Pls. XV, XVII, XVIII). Plain jewelled belts are worn by the men clapping (Pls, XVII, XVIII). Rows of large pearls encircle the waist occasionally interspersed by square gems.

Although the Parthian belt was in general a narrow knotted ribbon, sometimes low, heavily decorated girdles may be seen depicted on statues of the second to third centuries A.D. from Palmyra and Hatra123. The jewelled belt was in turn adopted by peoples in the Early Christian and Byzantine periods124 and to the East as evidenced by a statue of a Kushan ruler and a Gandharan monument of the fourth century A.D. depicting donor figures 125. These wide belts adorned with precious stones seem to be a fashion peculiar to Taq-i-Bustan during the Sasanian period. On other representations in Sasanian art jewelled girdles appear but they are neither as elaborate nor as wide as those of the hunting reliefs126.

The clapping nobles and the arrow bearer in the boar hunt relief are depicted wearing a jewelled belt partially covered by a long strip of material (Pls. XV, XVIII). The cloth is heavily embroidered and hangs down the front of the caftan. This feature also seems to be rare in Sasanian art and can only be compared to the garments worn by the courtiers of Khusrau I in the plate of the sixth century A.D. in the Hermitage Museum (Fig. 11)127. Here too the nobles wear a band of decorated material over the girdle which falls down the front of their robes.

120

HEADDRESSES WORN BY THE KING AND NOBLES

IN THE BOAR AND STAG HUNT RELIEFS

A discussion of belts now leads to the investigation of yet another mode of costume which seems peculiar to the site of Taq-i-Bustan. The headdresses worn by the clapping men in the boar hunt relief and by the king in both hunting reliefs are unparalleled in Sasanian art. The king does not war the usual elaborate ceremonial crown but a small flat, square cap more suitable for the hunt, which is tied at the back with short ribbons (Pls. IV, XIV, XIX) The two bearded clapping nobles wear similar hats, one of which is decorated by a double row of pearls (Pl. XVIII). A silver plate from Kodski Gorodok in Siberia, which stylistically seems to date from the sixth to eighth centuries A.D., is decorated at the rim with scenes of figures hunting bear, stag, and lions128. The men wear caps that are very similar to those represented on the Taq-i-Bustan relief. They too are small, box-shaped and tied at the back with fluttering ribbons. Prudence Harper has pointed out that the flat cap appears on late Sasanian coin representations incorporated with the royal ceremonial headdress. This form of the crown may have been introduced by Khusrau II himself, as it is found only on late coins of the Sasanian period129.

Although the evidence is not in any way conclusive it would seem that the cap, which does not appear on other Sasanian representations except late coins, was probably an importation from nomadic peoples since the closest parallel is a plate from Siberia. Its small, compact size made the headdress eminently suited for peoples who spend their life on horseback.

Thus the costumes worn by the figures in the hunting reliefs of Taq-i-Bustan represent the grafting of foreign elements on existing Sasanian tradition. Here one finds garments influenced by styles created outside of Sasanian Iran. The West, which played such an important role in influencing fashion in the early years of the Empire, is the source for the Classical garment worn by the female harpists, and the garments of the servants and mahouts. It is the East, however, that gives birth to the greatest number of types of costume which find their way at last to Taq-i-Bustan. The forms of the male garments, the stiff embroidered caftan, the belt with thongs, the high boots, leggings and hunting cap all stem ultimately from the East. The reliefs of the boar and stag hunts at Taq-i-Bustan then would seem to represent the assimilation of foreign influences and fashions, thus in some measure reflecting the existing political and economic climate of the period130.

The large grotto must have been carved during a period when Iran was receptive to foreign influences, a period of commercial and cultural exchanges with the peoples of the West and, more especially, with the kingdoms to the East. During a time when the dynasty was relatively wealthy such fashions as the caftan, boots and thonged belt could have been adopted. According to Erdmann, the Taq-i-Bustan grotto was carved in the fifth century A.D. during the reign of Peroz. The years of rule under this ill-fated monarch were years of suffering for the people of Iran.

121

Terrible droughts and famine caused the ruler to import food for the first time into the country127. Disastrous wars against the Hephthalites emptied the coffers of the Empire and finally, after a series of humiliating defeats, Peroz himself lost his life at the hands of the Hephthalites in 484 A.D. 132. It is difficult to reconcile these historic facts with the great wealth of Eastern influences found on the reliefs of Taq-i-Bustan. Would a country when bankrupt, its people starving, its eastern borders disrupted by continuing attacks, be either able or willing to carry on peaceful relations through trade or other exchanges with lands to the East?

After the reign of Peroz the Sasanians were no longer their own masters but were under the overlordship of the Hephthalite kings. They paid the White Huns yearly tribute and could not prevent them from interfering in Sasanian internal affairs. Kavad I (488-97; 499-53l A.D.) maintained the throne only through the aid of the Hephthalite king. It was not until the reign of Khusrau I (531-579 A.D.) that Hephthalite power was finally crushed with the aid of the Turks and that normal relations with the East could be reestablished 133. Khusrau I fostered economic and cultural exchanges with the Gupta Empire and sent his physician Burzoe to India to bring back Sanskrit writings, poetry, and books of medicine so that they might be translated into Pahlavi. It was during his reign that both chess and the tale “Kalila and Dimna” were brought into Iran 134.

The doors to the East had at last reopened and influences from the East that must have entered Iran much earlier through the silk trade and relations with the Kushan Empire began again to travel West.

Khusrau II, grandson of Khusrau I, fell heir to these favorable conditions to the East. Although his reign contained the seeds of destruction for the Empire, it was a seemingly glorious one. Great conquests to the West combined with successful campaigns against sporadic attacks in the East. The king himself lived in great splendor, his riches becoming legendary. It would appear that Khusrau II’s reign was eminently suited to produce the reliefs of Taq-i-Bustan. The East, opened up once again by Khusrau I, would have appeared to the pleasure-loving monarch as an endless treasury of exotic and costly goods to adorn his person and his court. Such fashions as heavily embroidered caftans bejewelled belts, and boots would have appealed to the luxurious tastes and jaded palates of the royal court.

Thus it appears that the historical climate of the rule of Khusrau II in the sixth to seventh centuries A.D. was suited to the adoption of foreign fashions. Khusrau II had the wealth, taste, and political opportunity for contact with peoples which would lead to the adoption of such costumes as those found on the figures in the boar and stag hunt reliefs. Peroz seems to have enjoyed neither the propitious historic events nor the riches necessary to foster peaceful relations with the East.

More than the historical evidence, however, which at best can only be conjectural, is the evidence of the costumes themselves. Many of the garments at Taq-i-Bustan make their appearance in Sasanian art only in the closing years of the dynasty. The embroidered caftan of stiff material with its skirt descending on the sides in points is not seen on Sasanian representations before the

122

reign of Khusrau I in the sixth century A.D. The same is true of the high boots and the belt covered with a panel of material. Belts with thongs do not appear until the seventh century A.D., shortly after the fall of the Empire. Indeed, certain features even appear to be unique to this site and do not occur again in Sasanian art. Thus the high collars on the robes of the female harpists and nobles and the headdresses worn by both men and women seem peculiar to Taq-i-Bustan.

It would seem then, that a majority of the costumes portrayed on the boar and stag hunt reliefs were adopted late in the Sasanian period, many in the sixth century A.D. at a time when Khusrau I’s conquest of the Hephthalites and friendly relations with India and the East would naturally have given rise to the adoption of foreign fashions. The evidence then, gathered from the study of the costumes of the hunting reliefs and taken in conjunction with certain historical facts, would appear to indicate that it was in fact Khusrau II who had carved the boar and stag hunt reliefs in the great grotto of Taq-i-Bustan. The king in the reliefs, surrounded by his nobles and harem, his servants and elephants, is an illustration in stone of accounts given of him by Arab historians. Tabari, describing his wealth, says that the king had 3,000 concubines, 1,000 serving girls, 8,500 war steeds, 760 elephants and 12,000 pack mules. His greed for jewels and costly vessels and garments was insatiable135. The king on the hunting reliefs at Taq-i-Bustan, clad in rich jewels and costly robes and accompanied by his glittering court, is Khusrau II who called himself “An immortal man among gods and a very powerful god among men, possessor of a sublime renown, he who rises with the sun and gives to the night its eyes 136”.

The above constitutes the first part of a two-part article. The conclusion will appear in this publication at a future time and will treat selected textile motifs which decorate the garments of the figures on the hunting reliefs of Taq-i-Bustan. Both foreign influenced and purely Sasanian patterns will be dealt with in an attempt to clarify further the position of these reliefs within the context of Sasanian art.

123