| The Chest Harness

Known as the 'Varangian Bra' by Stephen Francis Wyley |

|---|

The chest harness known as the `Varangian Bra' is a leather harness consisting of a breast strap with two shoulder straps going over each shoulder, connecting the front and back of the breast strap 1. There are a number of supposed depictions of the chest harness appearing in a number of pictorial sources of Byzantine origin but fails to be mentioned in any of the military manuals of the period 2. The questions are: did this piece of equipment originate in Persia and was later adopted from the Persians after interaction in warfare; or was it just a development of the stylized form of Byzantine art depicting a piece of classical body armour, and does this research effect the use of such a chest harness in historical re-enactment of the period.

There was a fair amount of information transfer between the Byzantines and the Persians around the 6th and 7th century. Haldon agrees with Dennis that the Byzantines made frequent adaptations of their foes' arms, armour and tactics 3. The evidence that the Persians had a chest harness first is provided by three dishes from the between the 5th and 7th century depicting three Sassanid kings hunting using a recurve bow 4. The Persian chest harnesses depicted on the dishes have a circular disc in the centre of the chest, which would suggest a central buckle 5 (See figure 1.) whereas the Byzantine sources show no such arrangement. The Byzantine sources showing both front and rear views of soldiers wearing the chest harness but not showing any evidence of a buckle, so the way in which such a harness would have been done up is unresolved (maybe the buckle is under an arm).

As previously stated, there was a fair amount of information transfer going on between the Persians and the Byzantines, this could easily have included a version of the chest harness. The fact that the chest harness is not mentioned by any military writers of the times could be put down to either; the chest harness was not officially part of a Byzantine soldier’s panoply or that it was only a provincial accoutrement beneath the notice of the treatise writers.

Figure 2. A piece from a 10th century Byzantine ivory chest showing a number of Skutatoi wearing the chest harness over what appears to be lamellar and the two Skutatoi are wearing the chest harness over either gambeson or solid leather armour (Victoria and Albert Museum, London).

Figure 3. Another 10th century ivory panel depicting Skutatoi, the armour differs from figure 2. with the addition of pteruges to the corselets (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York).

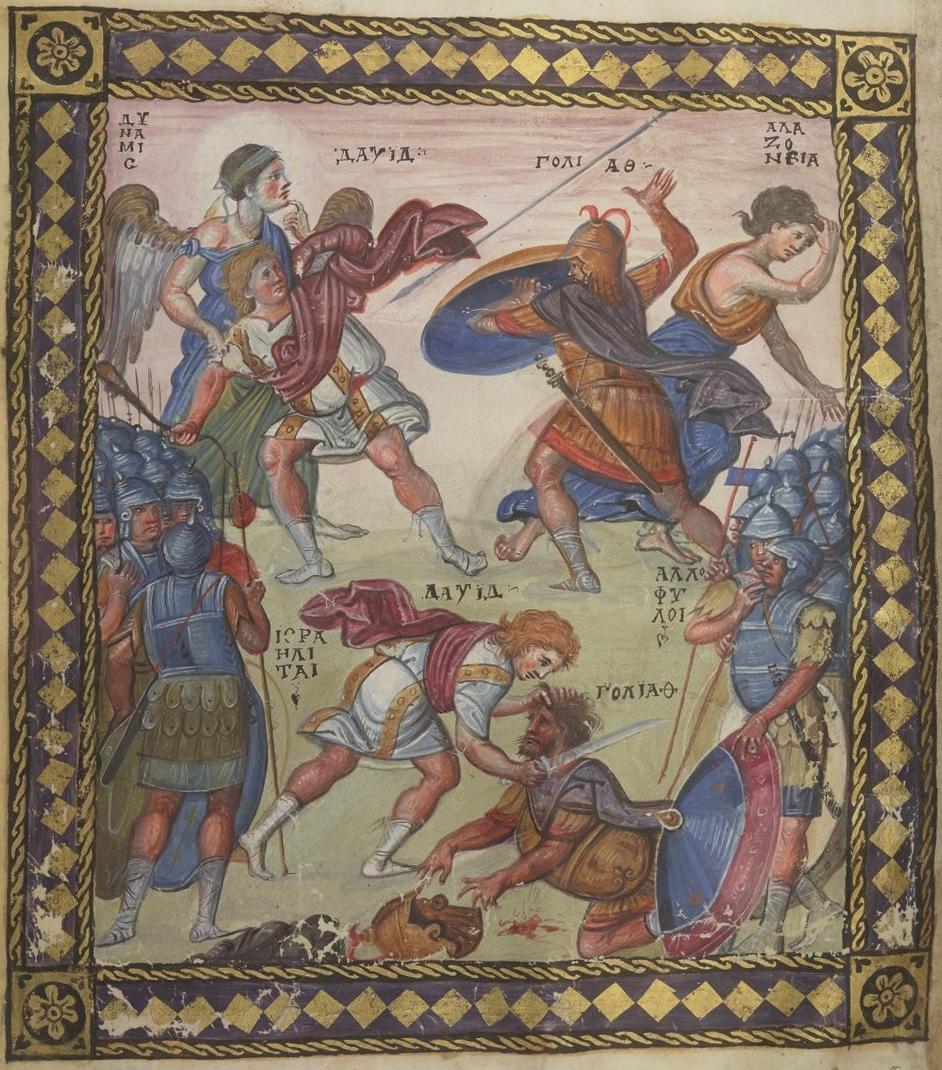

The second theory as to the possible origin of the chest harness is that it was actually a development of stylized manuscript depiction of classical body armour. If you compare the Roman soldiers shoulder and torso armour (lorica segmentata) depicted on Trajan’s Column with the armour in the 10th century illumination of David & Goliath from the Paris Psalter, then look at the later depictions showing the chest harness you will see the striking resemblance. See figures 4 & 5. If the Byzantine artists follow convention and copied previous works, with variations over time the shoulder and torso armour could become what some believe to be a chest harness.

Figure 4. Roman soldiers cutting trees from Trajan’s column (Rome AD 113). Note how the body armour is represented.

Figure 5. The 10th century illumination of David and Goliath from the Paris Psalter (Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris). Note the way the armour covering the shoulder is illustrated.

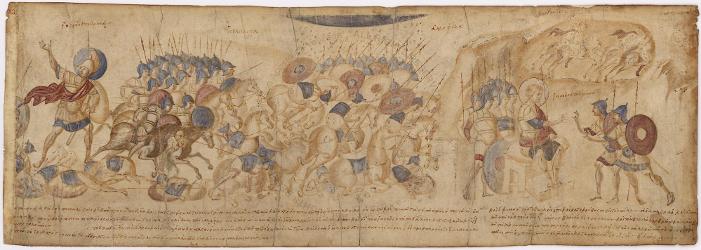

According to Heath the Joshua Roll (c.1000) shows both infantry and cavalry wearing the chest harness. See figure 6. The two ivory panels (Figures 2 & 3) indicate that the chest harness was used either over lamellar, scale, solid torso armour (eg classical body armour) or padded armour, but not mail. It also does not appear to be attached to the shoulder piece of the armour worn underneath.

Figure 6. From the Joshua Roll (dated to the first half of the 10th century (Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Rome). Note the appearance of the body armour on both infantry and cavalry.

Angus McBride’s drawing and Heath’s accompanying explanation of a Varangian (F2) argues that a Varangian who after long service in the body guard would have changed or renewed his equipment from Byzantine sources, and would have obtained such a chest harness. The only evidence Heath uses to support this theorem is that Anna Comnena wrote that the Varangians took full advantage of the Imperial arsenals to supplement their own equipment.

If the chest harness did actually exist then I am in favour of the Persian connection, whereas the transition in Byzantine art needs more proof. If the chest harness was a regular piece of Byzantine Army equipment then is was more that likely worn over lamellar or scale. However, the lack of mention in the Military treatises makes its official use questionable. The question of where the buckle was situated is still un-resolved and so someone else will have answer that question.

It cannot be stressed enough that primary sources must be used first in any such research and secondary sources (eg. Heath’s Byzantine Armies) used only to support your arguments.

Bernstein, D.J., The Mystery of the Bayeux Tapestry, London, 1986.

Dennis, G.T., Trans., Three Byzantine Military Treatises, Washington D.C., 1985.

Dennis, G.T., Trans., Maurice’s Strategikon, USA, 1984.

Haldon, J.F., Some Aspects of Byzantine Military Technology from the 6th to the 10th century, Byzantine & Modern Greek Studies, Volume 1, 1975.

Heath, I., Armies of the Dark Ages, 600 -1066, Sussex, 1980.

Heath, I., Byzantine Armies, 886 - 1118, London, 1986.

Humble, R., Warfare in the Middle Ages, London, 1989.

According to recent discussion with my peers, the Bayeux Tapestry is also a supposed source showing a chest harness. By popular belief the square shown on the chest of some of the Norman Knights is the mail flap which when tied in place protects the throat and chin of the wearer (an early version of the ventail). There is however also one Norman warrior pictured in the early part of the tapestry where Duke William, Harald and the Duke’s knights set off to punish one of Williams vassal’s in Brittany, who appears to wearing a harness over his mail shirt rather than the square depicted on the chest of his fellows. This should be viewed with caution since it could be put down to simply a variation in the artistic representation of the mail ventail. See figure 7.

Figure 7. Duke William heading of to castigate some of his vassal’s in Brittany, note the chest of his armour. It could be a chest harness (Bayeux Tapestry).

1 The actual origin of the name 'Varangian Bra' is uncertain other than it is inferred by Heath.

2 Ian Heath, Byzantine Armies, p36. Heath uses a number of ms and ivory panels to support the existence of the chest harness, such as: The Joshua Roll, Constantinople, c.1000, Rome, Vatican City, The Biblioteca Apostolic Vaticana, MS palat. gr. 431. Ian Heath, Byzantine Armies, pages 5 & 30. Panel from ivory casket, Victoria and Albert Museum, London, Ian Heath, Byzantine Armies, p34. 10th century ivory panel, Metropolitan Museum of Art, gift of J.Piermont Morgan 1917,

3 J.F.Haldon, Some Aspects of Byzantine Military Technology from the 6th to the 10th century,

Byzantine & Modern Greek Studies, Volume 1, 1975. pages 12, 15, 18, 19, 20, 24 & 46. "The Byzantine development was a combination of late Roman, Steppe, and Persian Styles" p.46.

George T. Dennis, Maurice’s Strategikon, USA 1984, pix, "The Romans learned from their enemies, Teutonic or Persian, and turned their weapons against them. "

4 Richard Humble, Warfare in the Middle Ages, the C.M.Dixon collection.

Humble shows three Sassanid kings.

1: p 18. A gold Sassanid dish, shows King Groz (AD 459 -84) hunting with a recurve bow on foot.

2: Ibid p.18. A similar Sassanid dish depicting King Ardashir III (AD 628-30) hunting with a recurve bow on horseback.

3: Ibid p.42. A 6th/7th Persian dish depicting a Sassanid King hunting with a recurve bow from camel back.

5 Ian Heath, Armies of the Dark Ages, p 101. According to Heath, the late Sassanid Clibanarias armour included a breastplate which was secured by straps which crossed at the back and did up at the front by means of a clasp on the chest (eg. the equestrian relief of Chosroes II at Taqi Bustan).

| Copyright © Stephen Francis Wyley 1998 - 2002

svenskildbiter@angelfire.com |