THE Turkish crescent, which must still be regarded as one of the luminaries of the military hemisphere, shone most resplendent during the reign of Solyman the Magnificent; unlike the mild and beneficent influence of the planet, of which it bears the image, it glared for a long period with the portentous aspect of a meteor, on the Christian nations, who had to seek safety in leagues and confederacies; nor has much more than a century yet elapsed, since it required the genius of Sobiesky to check its progress under the walls of Vienna.

The glories of the crescent appear, for a considerable time past, to have been on the wane. This declension has doubtless been produced, in some degree, by a neglect of the discipline which formerly enabled it to triumph; but is also owing in a still greater measure to an external cause: it is not that the Turks know less of the art of war now, than they did in the more glorious periods of their history; or, that the soldiers which compose their armies, fail in the requisites of strength, courage, and hardihood; but that the European nations have made greater proportionate advances in military knowledge, whilst that of the Turks has remained comparatively stationary since the days of Solyman; during whose reign, all the cotemporary Christian authors, are reluctantly obliged to confess the superiority in the knowledge and practice of the art of war, possessed by the disciples of the koran.

Another cause of the declension of the military power of this great empire, may perhaps be found in the little cohesion which exists between its parts. The rays of despotic power which can vivify every energy, and command every resource in the immediate vicinity of the Ottoman throne; diminish their influence as they diverge, until they are lost in the extent of empire; and the monarch whose frown is death at Constantinople, not unfrequently finds his power derided, and his Majesty insulted in the murder of the Capidgi, who bears his imperial mandate, by the Pachas and Beys of the more distant provinces.

Four hundred families, or tents of Turkman Tartars, established in the 13th century, at Surgut, on the banks of the Sangar, by the father of Othman, (from whom the present Turks derive their national appellation) form the narrow basis on which the superstructure of Ottoman greatness has been raised; under a succession of able and warlike princes, of Amuraths, Solymans, Achmets, and Mahomets, their dominion has been extended, till the Ottoman sway is acknowledged over some of the fairest portions of the three ancient divisions of the globe; in Europe, the Danubian provinces, Greece and its Archipelago, with a part of the lesser Tartary; in Asia, Syria and the Holy Land, Natolia, Diarbec, Irac, Armenia, Curdistan, and a part of Arabia; in Africa, Egypt, and the Barbary States: in fine, from the banks of the Dniester, and the shores of the Black Sea, to the confines of Nubia; and from Morocco to Bassora, on the Persian Gulph; the Ottoman dominion is recognized with more or less reverence and submission.

The military supporters of the empire were divided by Solyman the Magnificent, into the Capiculy, or soldiers of the Porte, or capital; and the Serrataculy, or soldiers appointed to guard the frontiers. The Capiculy compose what may be strictly termed the standing army; they are raised and paid by the Porte, (and as the same causes in all ages produce the same effects) like the Praetorian bands of ancient Rome, they not unfrequently give law to their masters.

The Serrataculy partakes more of the nature of a militia, the chief strength of it consisting in the Timariots, which are a sort of military fiefs, held on condition of bringing a certain number of soldiers into the field when called upon.

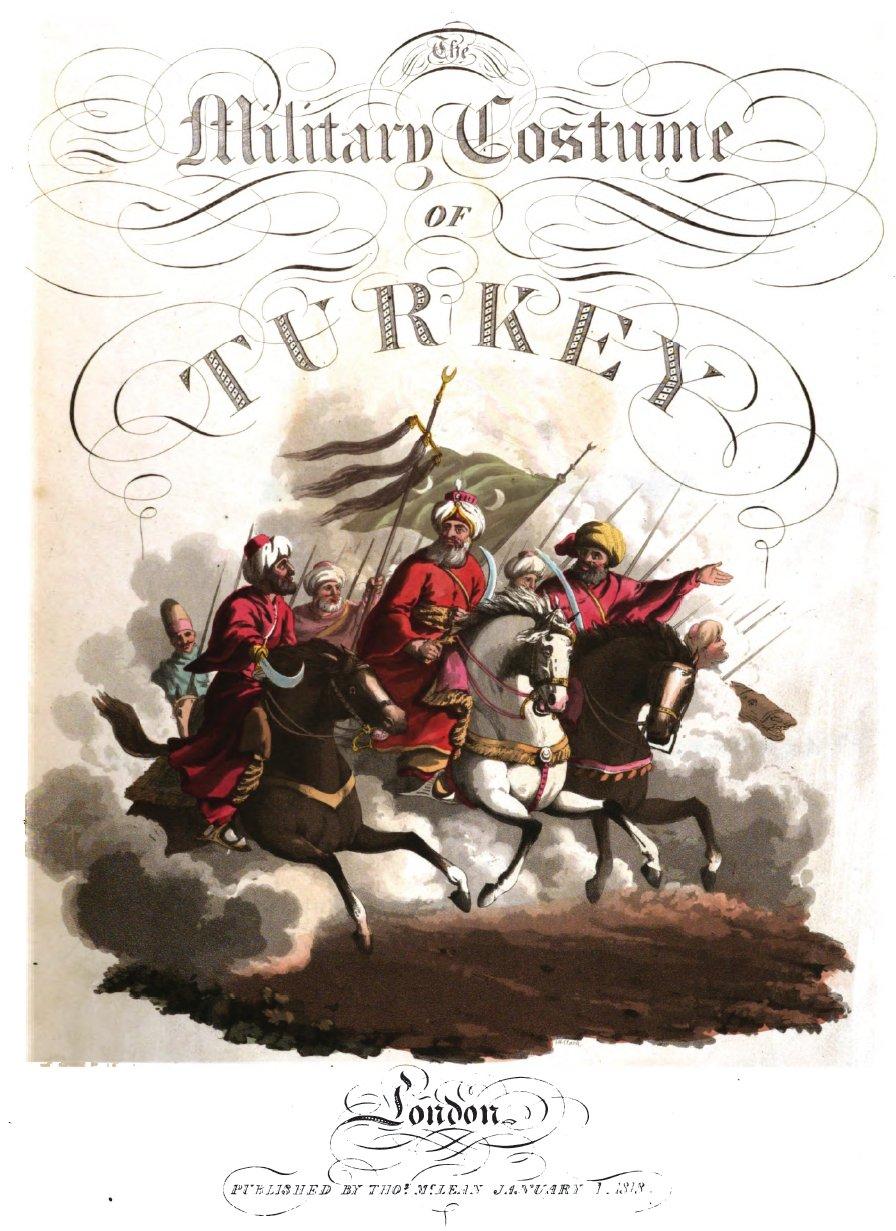

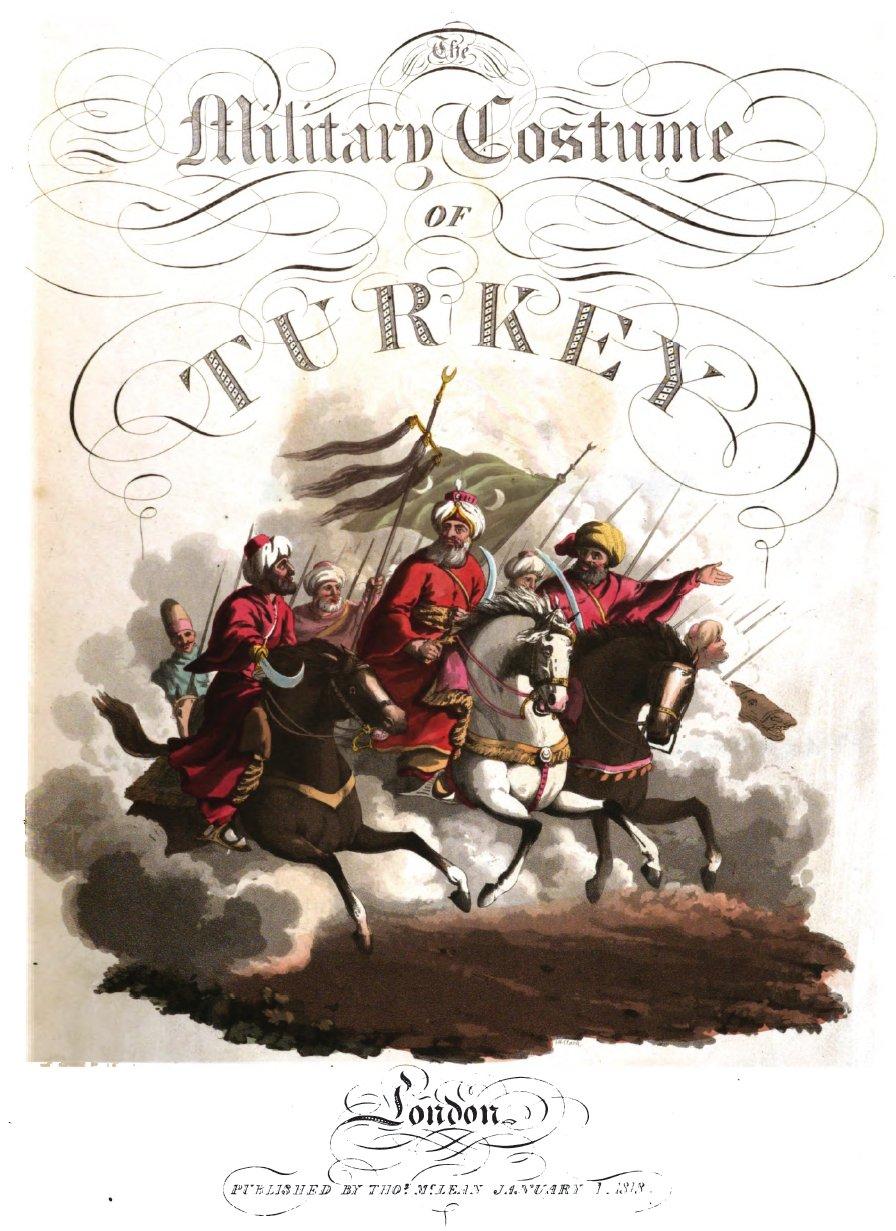

The collected force of the Ottoman empire is said to amount to 400,000 men. The Janizaries are infantry, and the Spahis cavalry; they have each of them their Aga, or chief; a Seraskier, or commander-in-chief, must be a Pacha of three, or at least of two, horse tails, which ensigns of his dignity are displayed in a very conspicuous manner before his tent, which last is of a green colour. Whenever the Grand Seignior takes the field in person, the companies of the different trades at Constantinople, are obliged to make him presents in proportion to their ability; on such occasions the sacred banner which is named Sandjakcherif, or the standard of the prophet, and which is of green silk, is carried to the army with great ceremony.

As the countries from whence the Turkish armies are recruited, are distant in situation, as well as different in manners and customs, it will be proper that a few of them should be briefly touched upon, as introductory to the explanations which are annexed to the subjects composing this work.

Of the natives of the Danubian provinces, it may be observed as singular, that they have in different ages furnished the troops wherewith their country has been held in subjection. The armies of the ancient Roman emperors were recruited with the hardy peasantry of these provinces, and, in the present day, their Turkish masters still draw their most valuable soldiers from the same source; from the time of the first

Amurath, the Sultans were persuaded that a government of the sword must be renewed in each generation with new soldiers, and that such soldiers must be sought, not in effeminate Asia, but among the hardy and warlike nations of Europe.

The provinces above-mentioned became the perpetual nidus of the Turkish armies, and when the imperial fifth of the captives was diminished by conquest, a tax of the fifth child was levied for this purpose on the Christian families; such were the sources from which the grandson of Othman formed a body of troops, which, under the appellation of Janizaries, at one time threatened Christendom with subjection, and whose exploits have left on the page of history some of the brightest records of Mussulman glory.

The modern Grecians bear little resemblance to their immortal ancestors, except in personal appearance: it is by the Greek sailors of the Archipelago that the Turkish navy is navigated, but for the purposes of hostility Turkish soldiers are embarked.

The Tartars of Circassia, to great elegance of form, unite beautiful features, have considerable strength of arms, and are very slender about the loins, which is, in a great measure, the effect of wearing a tight sash from their infancy; they are active and powerful, and these gifts of Nature are improved by an education which fits the individual for war; they being trained to the use of arms from their infancy: but like all the Tartar nations, they are from their habits of life best adapted to carry on a predatory warfare.

Egypt is inhabited by a variety of people, Moors, Copts, Greek, Jews, and Franks, whose manners and customs form strong contrasts with each other. The Arabs, who are perhaps the most numerous, are distinguished by a physiognomy full of expression, muscular arms, and the other parts of the body more agile than beautiful, more nervous than well proportioned. The Copts, who are the descendants of the ancient Egyptians, are, in complexion, a sort of tawny Nubian, with flat faces, hair half woolly, disagreeable features, and ungraceful person.

The troops furnished by the Asiatic provinces are chiefly cavalry, the horses of which are generally of Arabian extraction, and are sparingly fed with a little barley and cut straw.

The martial music of the Turks is not of the most pleasing nature; enormous hollow trunks, beaten by mallets, unite a heavy noise to the lively notes of little timbrels, which, accompanied with clarionets and trumpets, make a very discordant sound.

The Turks are what may be denominated a handsome race of people, and those who have acquired a stature above the generality, are possessed of a considerable degree of elegance, joining with the proportions reckoned beautiful, a countenance of dignity and expression. Some of these advantages are perhaps derived from the nature of their costume, which, in numerous instances, is well calculated to give importance and even majesty to the wearer. A splendid turban, in rich and massy folds, surrounds the head; a loose and flowing robe, often of the most costly materials and exquisite beauty,

covers the form; a sash, which frequently exceeds the richness of the turban, is wound about the waist, but without compressing it; here the ataghan, the handjar, the pistols, &c. are worn, and suspended from which, is to be seen the highly valued Damascus scimitar. The complexion, touched by the scorching sun, is finely relieved by dark eyes, powerfully marked eyebrows, and mustachios, which give sternness and importance, to a physiognomy at once interesting and noble. Smoking is an universal practice amongst the Turks; their tobacco is of the mildest and most fragrant kind, and the pipe is frequently highly decorated and valuable. The length of the tubes through which the smoke ascends, the odoriferous nature of the woods of which they are composed, the amber mouth-piece, and the fragrance with which the tobacco is impregnated, render this not merely a pastime, but a luxurious enjoyment; it seems indispensable to a military life, since throughout the empire this propensity to smoking is equally indulged by the highest as well as the lowest ranks.

The Turks are excellent horsemen, and must be considered as very formidable cavalry: their dexterity in the use of the sabre, and the command they have of their horses, (notwithstanding they ride what would here be deemed short) is such, that instances recorded where oxen have been deprived of the head by a stroke of the sabre. The Mamelukes are trained from their infancy to military evolutions, and display astonishing skill in the exercise of the javelin. The Arabian coursers are taught to perform their various manoeuvres with wonderful facility; a simple snaffle and rein are sufficient to direct them in their swiftest evolutions, although they possess all the fire and strength so esteemed in that noble animal.

The children of persons of rank are inured to warlike pursuits, from an idea that no glory is comparable to that which is acquired in war; and such is the effect of inculcating military habits, that it is usual for horsemen to approach each other at full speed, and halting suddenly, fire a pistol in the air, which salutation is considered as complimentary, while it at the same time conveys a proof of the riders' dexterity.

The love of military parade and of devotedness to the profession of arms, is conspicuous in the youth of Turkey; and though the precepts of the Mahometan faith may have a tendency to render them haughty, it is usual to meet with Turks of a distinguished rank, kind, affable, and possessed of great urbanity. The ceremonies of religion are regularly attended to, as well in camp as in other situations; prayers are said at sun-rise, at nine, at noon, at two hours before sun set, and at its setting: cleanliness being considered essential to devotion, ablution of the face and hands is performed, previous to each repetition of prayer. In the common ranks, the men are hardy, courageous, and capable of enduring great fatigue, under privations of every description; their ordinary diet consists of a small portion of bread, with a limited allowance of cheese, onions, olives, or oil; as either of these articles can be more conveniently procured: animal food they are not much in the habit of eating, though there is no religious objection to a gratification of that kind. Pillau forms a part of

their diet; coffee and tobacco constitute their indulgencies, and water is their ordinary drink. Wine is disallowed by their religion, yet when the prohibitions of the Koran have proved too feeble to restrain the desire of the longing Mussulman, the luscious bowl has been drained of its last sparkling drop with the avidity of a true Bacchanalian.

Persons from all parts of this immense empire, united in the pursuit of military distinction, present a strange association of figures and difference of hues. The Military Costume of Turkey, therefore, comprises a great variety of dresses, as well as men of countries distant from each other, and varying in their complexions from the scarcely tinged Georgian, to the sable Nubian.

The subjects which compose this selection, have been furnished by the liberality of a gentleman, who had stored his portfolio during his residence at Constantinople.

The portrait of his Excellency the Ottoman Ambassador, is engraved from a likeness (in the possession of the publisher) for which his Excellency had the kindness and condescension to sit in his robes for this express purpose.

London, January 1, 1818.

Portrait of His Exellency the Ottoman Ambasador.

1. Grand Vizier.

2. Capitan Pacha.

3. Pacha.

4. Capidgi Bachi.

5. Janizary

6 Ditto of a different Ortah or Regiment.

7. Ditto of Arabia Felix.

8. Ladle Bearer of Janizaries.

9. Colonel of Janizaries.

10. Offcer of ditto.

11 Military Chief of Upper Egypt.

12. Bey.

13. Mameluke of Egypt.

14. Ditto officer.

15 Ditto of Constantiuople.

16. Ditto of Grand Seignor.

17. Ditto of Grand Vizier.

18. Light Cavalry.

19 Spahis.

20. Officer of ditto.

21. Ensign Bearer of ditto

22. Soldier of Turkish Artillery.

23. Officer of ditto.

24. Officer of European Infantry.

25. Soldier of ditto.

26. Soldier of Albania.

27 Arnaut Soldier.

28. Soldier of Caramanian Waiwod.

29. Bostangi.

30. Officer of Turkish Police.