Register a SNAP EBT card with Amazon

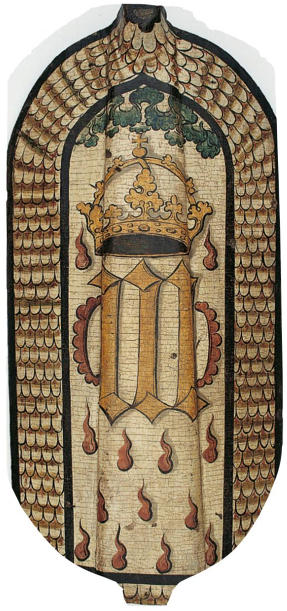

Hungarian 15th Century Shields

Hungarian Shield with Crow and Sun, late 15th Century

Front of a Hungarian Shield with Crow and Sun |

Back of a Hungarian Shield with Crow and Sun |

Grip of a Hungarian Shield with Crow and Sun |